Great Northern Divers - A Loon in Loon Land

- Gav Troon

- Jul 21, 2024

- 14 min read

The Great Northern Diver is a bird beloved of the North American state of Minnesota – so much so, they made it their state bird. Canada also proudly displays it on their currency. It’s known as the Common Loon over there, and common it is. This doesn’t detract from its dazzling beauty in the slightest, but here in Scotland it doesn’t breed, so is less accessible and more prone to unpredictable appearances – or so I thought before I took a trip to some of the remotest coastal areas of the Scottish Highlands. I had never before seen one in its beautiful, ornate summer plumage so, after a tip off and what amounted to a three-day whistle-stop itinerary from a couple of fellow diver enthusiasts, I became a great northern driver, and being based in an area of Doric-speaking origin, I was a loon (a man or boy) in the land of the loons! It was also a seventh heaven.

The very name – Great Northern Diver – is as wild, mystical, and romantic a name as it gets for a bird, to me at least. Their north is Iceland, about 600 miles away and it's the nearest breeding ground to where I began my journey around Scotland’s most north-westerly tip. From there their grounds spread west to Greenland, Canada, and the bordering US states comprising New England, right over to Alaska. What I did not know was that many of these (most-likely Icelandic) birds will holiday in Scotland all year if they are non-breeders – that is to say, not yet in full maturity – so the chances of relaxed encounters with them in the month of May were looking good. I was hoping for more than just picking out small specks of birds on the sea for I’d been told they would be close to shore in good numbers. When I arrived at Loch Eriboll at dusk, one of their hotspots, I realised I’d built up an expectation of a much smaller area of water, possibly teaming with birds. And, pondering how I could possibly cover such a large area in a single day, I found an off-road spot, enjoyed the feelings of peace and smallness in such a towering, rolling wilderness, and went to sleep.

The first thing I woke to at 6.45am was the call of the loon – at least I thought I did. I swear I did. There is no mistaking the spooky wail of these birds, sometimes described as a yodel. My fellow diver-loonatic had messaged the night before hoping I’d wake up to that very sound – had this come true, or was it entirely imagined? – wishful thinking at play? Something woke me, and if it was the bird I’d come to see, it must have been loud enough to wake me through a sealed car window. But there it was, two minutes walk to shore, a bird not yet resplendent in its summer costume, but a Great Northern Diver nonetheless. I’d never gotten out of bed so quickly before.

The bird that kick-started an epic dash around the NW coast of the Scottish Highlands from Loch Eriboll to Gairloch (above)

Before you pass this creature off as some sort of elongated duck, here’s a few facts because its facts are impressive:

True to their name, they really can dive, the record for a Great Northern Diver being a depth of 70 metres.

Stats recorded have them of the ability to stay underwater for anything between 1 and 3 minutes in a single dive, covering up to a possible quarter of a mile.

Despite their relatively small wings, they can fly at speeds of up to 75 miles per hour.

Less impressive are their short legs and large feet, set so far back on their body that they rarely utilise them for walking, having evolved into such adept aquatic creatures. This, and their weight make it harder for them to take off, meaning that they have to use a runway approach of flapping and skimming along the water before they can manage to get into the air.

Unlike most birds, Great Northern Divers have a number of solid bones (as opposed to hollow) that add weight to help them dive. This is only replicated elsewhere in puffins and penguins.

Historic evidence suggests that Great Northern Divers have been around for 20+ million years, making them the oldest and most primitive example of a bird alive today and one whose fundamental physiological structure has altered very little.

The beautiful red eyes are thought to aid their sight underwater, and in the breeding season these change to a much more brilliant red.

A large, dagger-like beak is perfect for catching or skewering prey underwater, which is where they mostly devour it, but can also be used to see off predators – Bald Eagles have been known to have been impaled by divers.

Records show individuals surviving up to 30 years, sometimes a little more.

Their calls are of such a volume that they can be heard from more than 600 feet away.

It’s a call that could easily penetrate through my car window, surely? I would be lucky enough to witness it again on this trip, but its suddenness, volume, and echoey ambience takes you by surprise, not to mention the absolute wildness and evocative other-worldliness of it. I urge anyone reading this who hasn’t heard it before to seek out a recording online – it might haunt you forever more. In the past, it haunted sailors who believed it to be the premonition of a storm. Red-Throated Divers are traditionally known in Gaelic culture as rain geese for their perceived ability to ‘call in the rain’ with their mournful song.

Divers out of season seem to generally behave passively and don’t flock tightly together with others, so there’s less need for vocalisation to attract attention to themselves. These non-breeders I was seeing were just that; mostly young, free, and single, just pottering around the shorelines displaying that classic diver behaviour of a constant dipping of the face underwater to try and visualise potential prey. They seem a very peaceful, gentle bird. But perhaps because of their inability to get out of the water quickly enough, they are naturally wary. So I had to curb my excitement. But I’d like to thank that one particular bird, if it did indeed wake me up that first morning!

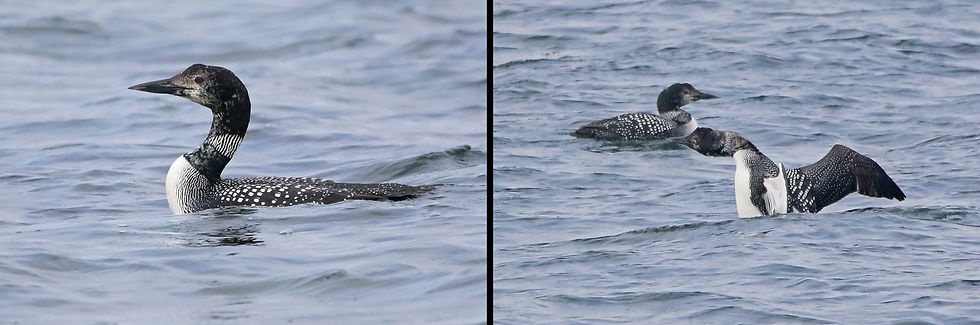

Great Northern Diver mid-moult on Loch Eriboll, May 2024 (above)

A walk along the shore produced a few more, one moulting into that spectacular summer featherage. The excitement was building and the effort was paying off already. Looking further out into the sea loch, I could see more in the shimmering, early morning light. One or two Black-Throated Divers were among them (it’s worth mentioning that there are only 5 diver species worldwide). Realising the scale of my operation, and feeling a little weary in the early summer heat, I headed back to base and back onto the NC500 route, which was mercifully quiet. Loch Eriboll is a place deserved of a full day’s diver watching as it turned out. Their plumage catches the light easily which makes the chance of spotting them from the window of a moving car fairly high. It’s just finding somewhere to stop that isn’t a passing place that’s the problem. Another beauty presented itself in not too long though, its moult into that plumage almost complete. It didn’t seem bothered by me, and I was able to advance in bursts when it dived underwater, then hide behind rocks as it surfaced. I felt as if in another world, honoured by the visitations of these creatures who don’t live here, but have travelled many miles to be here – and I felt the call of Iceland… Greenland… beyond! There are occasional unverified reports of Great Northern Diver breeding activity in Scotland, but the strongest record from 1970 concerns inter-species hybridisation between a Great Northern and a Black-Throated Diver, so it’s always worth studying the plumage for evidence of this. I can only assume the Great Northerns have decided that their current breeding grounds offer them the best chances in life, so that is where they will stay.

Great Northern Diver in near-summer plumage on Loch Eriboll, May 2024 (above)

Six hours later I headed west for 30 or 40 miles of beautiful, empty roadside views, hearing cuckoos wherever I went, for it was the season of their visitations also, from Africa, and they were everywhere! They come, they swap the eggs of small birds for their own, and disappear again almost as quickly as they arrive, like some unspoken admission of their guilt. Balnakeil Bay next to Durness was the next stop, and there were Great Northern Divers there too, catching flatfish and crabs.

Great Northern Divers with flatfish and a tiny crab at Balnakeil Bay, May 2024 (above)

From Durness, the road takes a sharp turn south and, already feeling nostalgic, I contemplated heading east back to Loch Eriboll. But that would have cut out a lovely swathe of classic north-west landscape, barren, littered with exposed rock, and occasionally peaty. I imagine it’s far from lovely outside of summer, but there’s an appeal to its starkly uninviting, uninhabitable and impenetrable features. It’s like the end of the line. There’s little or no civilisation here – all you have is wilderness, and if the rest of the country is eventually taken over by people and their need for homing, I doubt very much this area could accommodate, so hard is it. I wonder what tourists on the NC500 really think of it. It’s not the picture-postcard Scotland of Glencoe, Loch Ness, or Ben Nevis. It has no distinct landmarks or recognisable mountains as such – some would call it featureless perhaps. But May was a good time to go, not just for the lure of the divers who seem so appropriate to this untamable land, but the relative quietness of the road (yes, just the one!) Luckily there are adequate amenities along that singular road – petrol stations, shops, restaurants, bank machines and the like, so you won’t get caught out as I feared I would. My car accommodates a mattress in the back and after watching a pair of Red-Throated Divers as the sun was setting at a place called Scourie, and checking out another few potential diver spots along ‘the wee mad road’ to Lochinver (and it is mad – narrow, bendy, and very up and down), I found another off-road spot and settled down for the night once again. The divers at Scourie, by the way, did a classic diver thing of suddenly swimming off into thin air, never to reappear. It so often happens with these species. It must be their ability to dive long-range, and appear somewhere else out of sight. Spooky!

Red-Throated Diver against the setting sun at Scourie Bay, May 2024 (above)

I must mention Dave here – he who made the suggestion of visiting Loch Eriboll. Dave himself appeared, as if out of nowhere, the next morning, waiting for a boat out to Handa Island. I last met Dave on a boat trip out on the Moray Firth, looking, successfully, for White-Billed Divers the previous month. And as Red-Throated Divers flew around the bay at Tarbet, with that strange looking in-flight gait, heads bowed below the line of their long necks like a goose, there was Dave also! There were divers on Handa too, and rumours of more possible birds scattered all over the small and very numerous lochans buried amongst the landscape back on the mainland. I couldn’t find any, and headed south for more Great Northerns, and what would become the dream moment.

The B869 north from Lochinver eventually turns eastwards at Clashnessie and turns into that ‘wee mad road’. But before it does, it passes well known holiday spots such as Achmelvich and Clachtoll, mini tourist meccas offering caravan accommodation. There’s more people down here, but still every chance of diver sightings. Indeed, Red-Throated Divers were in Achmelvich Bay, not far from the swimmers and paddleboarders. But it was Clachtoll Bay that really delivered. It’s a gorgeous spot anyway, as you approach it either side from higher ground – a green, grassy expanse of paddock with lots of cute little crofts either side of the road, lambs running freely, and the varying colours of wild flowers everywhere you look. The caravans are beginning to take over and with people all around, I was beginning to think I’d already had the best of the divers. Also weary from driving long distance, maybe I could just go somewhere quieter? But the weather was exceptional and if divers were around, the sunlight had the potential to create some great photos.

Cue one Great Northern Diver peacefully fishing in a little cove off the bay, a few metres away. All the elements came together in that moment. Again, it was aware of a human presence, but its body language and behaviour was accepting. I managed to scramble down to the level of the water, the bird’s true aspect, for better photos, and a few hundred were taken as the bird alternated its position in the wee cove with being further out into the sea, and back. The sun was blazing down and the whole trip peaked right there! Or so I thought. Not to mention that this bird, save for a few pale flecks on its face, was in full-blown summer plumage. The light really brought out its full beauty – the deep greens of its feathers, and those red eyes. It was a fully immersive experience, and I forgot everything else for a while, just reveling in the wonder of nature.

The star Great Northern Diver at Bay of Clachtoll, May 2024 - in alarm mode due to a very noisy seagull (above)

After what must have been an hour, it did that disappearing-diver act, though I caught up with it again at Bay of Stoer, the next stop just around the corner, where there were more Great Northerns and a single Black-Throated Diver in its breeding plumage too. A couple more stops at Clashmore Bay and Clashnessie Bay yielded nothing and in some ways the trip felt over, in a good way.

Great Northern Divers in silhouette at Bay of Clachtoll (left) and Bay of Stoer (right), May 2024 (above)

I headed back down to Lochinver where another Great Northern Diver was pulling crabs out of the water of the bay and I had the strange experience of walking along the pavement of the high street watching it at close quarters for quite some time. At one point the bird stood up on the water to stretch its wings, a lovely sight and photo opportunity. And then my camera’s memory card ran out so I took that as a sign to move on. Fortunately, I had another, albeit smaller one.

Great Northern Diver at Lochinver Bay, May 2024 (above)

So I took off on the 2 hour drive down to Poolewe, an area I’d visited earlier in the year in March for the same purpose – divers! The route takes in another ‘wee mad road’ before it hits Inverpollaidh and the distinctive peak of Stac Pollaidh, and then down to Ullapool where you branch off past the scary-looking mountain called An Teallach before pointing toward Gruinard Bay, Aultbea, Poolewe, and Gairloch, the last stops of this diver odyssey. It’s an epic drive, visually, but the light was fading and I wanted to reach Poolewe before dark and park up at Firemore Beach. I made it, but there was some activity on the beach due to a washed-up Pilot Whale which had stranded earlier in the day, been refloated, but later died at sea having succumbed to starvation, a post-mortem concluded.

The deceased whale had been tethered to a post so it wouldn’t drift out on the tide and was still there in the morning as I watched yet more divers, a pair interacting briefly, and another group of three. There were more birds further north at Cove where the small road ends, but I was unable to get close to them as most of the land is fenced off for crofting right down to the shoreline. The west side of Loch Ewe has a few well-known spots for diver spotting – namely Firemore, Inverasdale, and Naast, but it was Poolewe itself where I was watching a pair of Red-Throated Divers fishing close-in at the shore when suddenly a Mallard duck splashed down next to them and one of the pair stood up on the water in alarm, craning its neck at a right-angle to its body in a manner that could only be threatening. Again, I am guessing it’s the diver’s lack of normal mobility that has made them have to adapt, and simply rising up on one’s feet with a display of imposing height does the job and uses less energy than a full-on attack. It’s these unexpected moments of fleeting behaviour that remind us this isn’t some pre-recorded viewing event, it’s raw, live-action that happens all the time – we’re just not there to witness most of it. But when we are…

Red-Throated Divers reacting to the sudden appearance of a Mallard (just out of shot), Poolewe, May 2024 (above)

It happened again at Aultbea, a short drive up the east side of Loch Ewe. A Red-Throated Diver splashed down near the pier and a few Great Northern Divers were also present close-by – things were good enough already. Around the corner at the slipway was another pair, seemingly disinterested in each other, fishing away. The slipway was allowing me closer views of them and I suppose the dilemma of the nature-watcher is when to walk away – to try and preserve the awe and excitement of the moment and not stretch it out too long so its overfamiliarity turns into mediocrity. Having a tight itinerary helps this along, but ideally you’re partly there in the hope of being released from the shackles of time – being at one with nature, in the moment, lots of moments! Things like a camera battery draining or a memory card filling up, though annoying, force us to consider our options, assuming we are photographers (though sometimes it’s nice to put the camera down once in a while). I was good for time though and was looking more to the birds themselves for behavioural signs that they were drifting away out to sea, otherwise I could have watched them fish all day long. I was half way back to the car when I heard the call – this pair of birds suddenly became very obviously interested in each other. Loud, wailing cries, craning of the necks, stiffening of the tail feathers, one bird standing up on the water flapping its wings – it was a fascinating, most sudden change of mood, and for all I know may have been two birds in conflict rather than mutual attraction. Whatever it was, it was once again a tiny moment which I could only have dreamed of – I hadn’t imagined these divers would be doing anything more than bobbing around eating and sleeping, that alone being a joy to see.

Great Northern Divers from Aultbea slipway, May 2024 (above)

And so what else was there? It was a moment that raised the bar so much. With what time I have, I would forsake most everything else for a few moments like this every year. Nature is a therapy, if we can truly tap into it, that is for sure. But we will never be anything more than spectators. This whole trip was about pushing the boundaries of wild – witnessing a passage of spectacular-looking birds from another land which is truly out there, on the fringes of wilderness itself. There is a typically-human comfort in knowing we can return from that wilderness with such tales as I describe here. Some may wish to feel they have conquered the wilderness. That would be great if one has the means, but I’m not sure where you go from there? We can realise our place, keep our humble distance, and be content following, observing, hoping for that special moment. These divers open up the world to me. They fire my imagination and I travel in my mind when I think of them. It sounds very self-absorbed. This trip confirmed their existence, and that dreams do come true – waking dreams, that is. They took me to the edge of my limited existence but also reinforced the idea that one need not travel far to witness such awesomeness. If you plan a bit, take some time, and dig in deep, riches can reveal themselves.

And so I bade farewell to Loch Ewe via a few more spots – tiny seashore crofting communities with funny names such as Mellon Charles, and Mellon Udrigle (mellon being the Anglicised Gaelic meallan meaning little hill), Ormiscaig, and Laide (where divers were seen) and headed south to Gairloch, the very last stop. Unless you are in the town itself where I’ve seen divers sail right past a café window, Gairloch Bay is a hard place to get close to them, so you have to be content with more distant views. I remember well my love of seabirds kicking off right here outside the youth hostel when I was around 10 years old, and the huge thrill of watching Black-Throated Divers from the clifftop back then. There were both Black-Throated and Great Northern Divers in the bay this time, and I wondered where the time goes and when I might return. In writing this, I know I’m already planning on becoming a pilgrim to these divers and the beautiful spots they inhabit, and each future experience will have its own, unique story – just not necessarily in a blog!

Excellent Gavin. I like your writing - personal, insightful, descriptive and above all honest. The photos too are good quality, especially the close up portrait of the GND.. A bit of a left field comment. I think you would enjoy times with Humpback whales - I found a spiritual connection with them when they came to the Ythan estuary way back in 2016. If you get a chance to spend some time with them it'll chnage you for the good! The poem by Mary Oliver entitled 'The Humpbacks' tells the story of her seeing them breach off New England and she describes her feelings and draws allegories about the meaning of life.

An amazing trip. So glad you spotted the divers. Your photographs are supberb.

I felt I was really there. Your description kept me thoroughly engaged throughout. Loved it. More please!

Got me thinking about how much of nature I glance at and miss the incredible stories behind it. Loved reading this!